The Library of Lost Books: Bringing the Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums Back on the Map

- Kinga S. Bloch,Bettina Farack

- Jan 11

- 7 min read

Preliminary Remark: The "Library of Lost Books" is an international project including an exhibition and an online-campaign. It aims to commemorate and educate about the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies in Berlin (Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums). The institute was both, a rabbinical seminary and the first research institute dedicated to Jewish Studies in Germany. The project documents the history of the university, the looting of the library by the Nazis, and the dispersal of its remains in the post-war period. It also includes a global citizen science project to trace the 60,000 lost works. Up to today books have been found in Germany, the Czech Republic (Prague), Israel, the USA, and in Great Britain. The Library of Lost Books is a joint project by the Leo Baeck Institutes in Jerusalem and London and the Freunde und Förderer e. V. Berlin. It is part of the Education Agenda NS-Injustice, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Justice and the Foundation EVZ/Remembrance, Responsibility, Future.

Public imagination about the history of lost places thrives on images of spatial rediscovery and exciting rescue missions. We picture the dramatic recovery of hidden treasures, spectacular revelations in murky corridors and basements, or even the navigation of ruins. But where and how do we start such a search when there is no physical place to go to in order to track down what was lost? What can one do when there is no map to follow because the place itself has disappeared, leaving nowhere to excavate precious objects from the past? And what happens if we are looking for items made of fragile materials, such as paper, that are not buried but displaced, circulated, scattered into the world? How do we search for a collection that survives only in fragments, without catalogue or address?

The library at the centre of this absence once existed as a physical institution, before its dissolution and dispersal. The Library of Lost Books project (2023-2025) is an attempt to address such issues. It engages with the fragmented remains of a unique library that once belonged to a Jewish community in the centre of Berlin: the Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums (1872-1942). The Hochschule was home to a rabbinical seminary educating rabbis based upon the principles of Reform-Judaism. It was also the first research institute dedicated to Jewish Studies in Germany. Its progressive and open approach to Judaism attracted scholars and students from all-over Europe who formed a vibrant and diverse community in the German capital. The institute was open to students and to intellectual exchange across faiths, often hosting lectures by scholars from the nearby University of Berlin. Topics studied at the Hochschule ranged from historical engagement with Biblical texts to modern questions such as whether women could hold rabbinical office and arguments for the universalism of the ethics of Judaism. Amongst its students and staff were prominent and innovative representatives of German Jewry such as Leo Baeck, Franz Rosenzweig, and the first woman rabbi, Regina Jonas, just to name a few. Franz Kafka frequented the premises and is said to have been particularly fond of the reading room.

A Unique Space for Jewish Learning and Scholarship

The Hochschule’s library reflected the manifold research interests pursued by its scholars and students alike. Holding approximately 60,000 volumes, including rare sources such as the Herlingen Haggadah (1729-1730) or the Luzzato Manuscript (Samuel David Luzzatto’s Synonymia Hebraica - Mavdil Nirdafim, c. 1815–1820), it was one of the largest collections of books dedicated to the study of Jewish history, religion and culture in Germany before 1942. Next to seminal works reflecting debates in contemporary Jewish studies, its collection also included materials chronicling the life of Jewish communities and institutions sent to the Hochschule from all-over the world, such as The Annual Reports of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, The Bulletin de L’ Alliance Israelite Universelle (Paris), or the Polish language quarterly Palestyna (1908) detailing insights into cultural and economic issues in Palestine.

Collage from the online exhibition featuring the façade of the Hochschule in Berlin in the post-war ruins of 1945

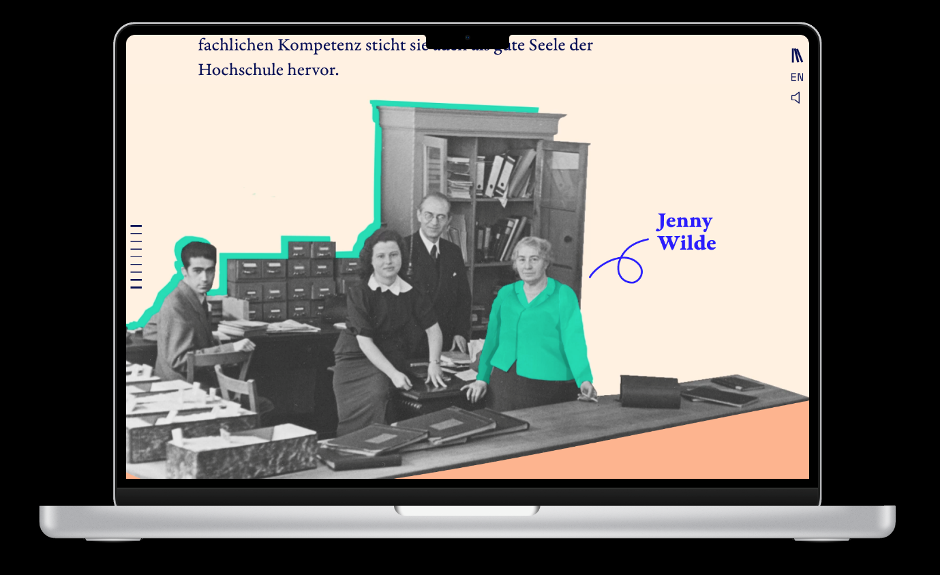

There is also evidence for manifold exchanges with German-Jewish institutions like the Jacobsen Schule in Seesen am Harz, the Israelitische Lehrerbildungs-Anstalt Würzburg, the Israelitische Vorschuss-Institut Hamburg and the Gesellschaft zur Verbreitung der Handwerke und des Ackerbaus unter den Juden im Preussischen Staate 1812-1898 just to name a few. The collection thus functioned not only as a scholarly resource but as a node in a transnational network of Jewish knowledge production and documentation. The library was cared for by a woman librarian, Jenny Wilde, likely the first female head librarian of an academic collection in Germany.

Jenny Wilde and her colleagues at the reference desk of the Hochschule library, ca. 1938, as featured in the online exhibition Library of Lost Books.

Destruction, Theft and Forced Labour

After almost a decade of duress under the National Socialist regime, this unique place of Jewish learning and its extensive library were forcibly closed in 1942. The books were stolen by official order and confiscated by the Department for so-called Enemy Research of the Reich Security Main Office. Some of the books and many members of staff were deported to Theresienstadt, where Jenny Wilde and others were forced to catalogue the books for the Nazis who wanted to appropriate and abuse them alongside many other Jewish collections for their antisemitic studies of Jewish history and culture. The library was thus forcibly transformed from a scholarly resource into an instrument of racialised knowledge production.

Addressing Post-War Dispersion

As there is no legal successor of the Hochschule, the books that have re-emerged after 1945 were distributed amongst Jewish organisations. Many volumes appear to have been destroyed, stolen, or inadvertently ended up in places all over the world. What was once a coherent collection, became a diaspora of individual objects, each entering new institutional, commercial, or private contexts. In some cases, books from the Hochschule have found new homes where they can be appreciated by scholars and the public alike, such as the Herlingen Haggadah at Leo Baeck College London or the books from Theresienstadt that are embedded into the collections of the Jewish Museum in Prague; however, such cases remain the exception rather than the rule.

One of the Hochschule’s books, showing some of the provenance markers it contains. Each trace is explained in this case study to guide book detectives in their search. Today, this book is part of the Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem’s library.

The post-war dispersal of the Hochschule’s books created a library without centre, catalogue, or institutional successor, existing only through the circulation of its fragments. The Library of Lost Books project is an attempt to draw attention to the fate of Jewish libraries that have been subject to systematic theft by the National Socialists. It reflects the broader condition of Jewish institutional collections that could not be restituted, because their institutions were destroyed. This project approaches the dispersed collection not as an irretrievable loss but as a dispersed library whose traces can be documented, connected, and made legible again. Central to this work is the reconstruction of provenance trajectories: identifying individual books, locating them in the holdings of their present custodians, and registering their movements over time. A public digital platform and international participation enable this reconstruction at a scale impossible within a single institution.

Mapping Against the Void

Collaborative research has involved libraries, schools, and volunteers across several countries. Public contributions have helped document about 5,000 books, each one added as a node in an expanding map of this post-spatial library.

The reconstruction of this collection faced various challenges: the absence of a comprehensive catalogue, the dispersal of books across many collections, heterogenous data reported by our nevertheless enthusiastic book detectives. Yet, individual volumes continue to surface. Each one carries traces of movement, ownership, and reuse. Taken together, these fragments do not recreate the original library, but they make visible the dispersed network that replaced it. This work suggests that the library did not simply disappear, it changed form. Its afterlife exemplifies what Markus Kirchhoff (2002) has identified as a defining feature of modern Jewish library history: the large-scale movement of books, through which Jewish collections were not only destroyed, but transformed through forced displacement and subsequent histories of circulation. Mapping these trajectories is not an act of recovery, but a way of writing these collections’ history from movement and rupture. Rather than restoring a lost whole, the task is to recognise the dispersed library as it exists now: a constellation of objects and their individual histories.

Kinga S. Bloch is a teaching fellow at the Department of History at Queen Mary University of London focusing on German-Jewish history and Cold War Europe. She is part of the team behind the Library of Lost Books and has been working on projects fostering the visibility of Jewish libraries since her time as deputy director of the Leo Baeck Institute London (2019-2024). Her publications include peer reviewed articles about the impact of television series on memory and societal discourse. She holds an MA in History and Philosophy from Humboldt University Berlin and has just submitted her PhD thesis about gender roles in TV series produced during the Cold War in East and West Germany and socialist Poland (UCL).

Bettina Farack is a PhD candidate at the University of Erfurt. Her dissertation reads the library of the Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem and the material histories of its books as evidence of forced migration and persecution, revealing central dimensions of the German-Jewish experience through provenance history. Bettina Farack has studied library and information science, philosophy and Protestant theology at the Humboldt University of Berlin. From 2019 to 2022, she managed the library and the archive of the Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem. From 2023 to 2025 she coordinated the project to create the Library of Lost Books. Her research focuses on library history, collection theory and provenance research.

Further Reading

Kinga S. Bloch, Bettina Farack and Irene Aue-Ben-David, ‘Mission (Im?)Possible: ‘Holocaust Education’ und Citizen Science nach dem 7. Oktober’, in: EVZ Magazin der Bildungsagenda NS-Unrecht, Nr. 3 (2025) https://www.stiftung-evz.de/en/what-we-support/education-agenda-ns-injustice/magazine-of-the-education-agenda-ns-injustice-2025/mission-impossible-holocaust-education-and-citizen-science-after-october-7-2023/.

Bettina Farack, Kinga S. Bloch and Irene Aue-Ben-David, “Library of Lost Books.” An online exhibition, https://libraryoflostbooks.leobaeck.org/, 2023. The Library of Lost Books project was generously funded by the EVZ Education Agenda NS Injustice (2023-2025).

Bettina Farack, ‘The End of a Library: The Wartime Fate of the Library of the Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums Library Collections’, Judaica Librarianship 23 (December 2024), 6-24. https://doi.org/10.14263/23/2024/1415.

Irene Kaufmann, Die Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums (1872-1942), (Berlin: Hentrich & Hentrich, 2006).

Markus Kirchhoff, Häuser des Buches. Bilder jüdischer Bibliotheken (Leipzig: Reclam, 2002).

Felix Steilen, Berlin in Cincinnati — Scenes from the End of the ‘Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums’, in: The Leo Baeck Institute Year Book, Volume 69, Issue 1, 2024, Pages 145–162, https://academic.oup.com/leobaeck/article-abstract/69/1/145/7738290?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Title Image: Still from the exhibition trailer inviting the public to search for the lost books. Have a look on You Tube

Comments